Intro

I’ve been keen to study the audacious 1980s endurance record attempts by two of my favorite manufacturers for some time now. Those two I’m referring to are, of course, Mercedes and Subaru. Each of these company’s endurance efforts have been discussed on their own, but to my knowledge, neither have been closely compared in any meaningful way to each other.

Let’s travel back to 1983. Catalytic converters didn’t exist and Americans were still pumping leaded fuel into their tanks which is probably why I have a weak memory now in my 40s and probably also why these cars ran as well as they did at full whack for four days straight. Mercedes was on a blitz to prove that their billion-dollar-baby-Benz was as good on the track as it was on the road and to do so, they set out to make a 50,000km endurance goal, governed by the FIA and run under their rules at Nardo, a race track in Italy that looks like a giant ring from space; a perfect circle almost 8 miles long, designed for this exact thing- high speed running.

We’ll get into details later but many records have fallen at Nardo, and on this four day span in August 1983, Mercedes would set three FIA records, a 25,000km, a 25,000 mile and a 50,000km distance record. The gravity of this event, if you’re into this kind of thing, is that only one year earlier in (you guessed it) 1982, a Porsche 928s made a 24 hour record going only 1mph faster than Mercedes did for the entire 50,000kms. Amazing.

Laying more groundwork for this comparison, 6 years later, in 1989, a little manufacturer from Japan set out on achieving it’s own lofty goals, in this case a 100,000km endurance record by, you guessed it, Subaru, which was to take place in Arizona at a place called the Auto Test Center at Stanfield.

The track was owned by Nissan and in part, by Calsonic whom with Subaru had a business relationship. Stanfield is an oval, not a circle but it’s banked and long at almost 6 miles. Subaru achieved this record in what’s said to be 447 hours which is roughly 18 days of driving non-stop. Subaru used 24 drivers (!) to do this. (Mercedes used 18 drivers for half the distance) I’ve read some articles that suggested rain thwarted the Subaru effort which would explain why some dates published say that they raced for 21 days. My guess is that they threw away a few days on the front end due to the rain. Subaru did 138mph average for this entire time, pit stopping for reasons similar to Mercedes. Subaru used three Legacy, just as Mercedes used three 190e. The Legacy were equipped with the EJ20G engine and not the US EJ22. Here I am, already getting into the details.

Let’s compare.

The Subaru team was not holding back. They flew what appears to be 4 cars from Japan to SLC and then transported the cars from SLC to AZ where they set up an enormous base camp with spares, tents, porta-potties and more.

It looked like there were two semi-trucks full of spares and two tanker trucks on hand full of fuel. The team received formal briefings and looked very organized, strikingly similar to Mercedes years before. Both teams logged data extensively and used both high tech and low tech methods for the time.

Listening to the boxer rumble as the cars set off for days of flat out driving.

Mercedes used a camper van next to the track and an old W123 Wagon to hold electronic equipment to track progress and the car’s condition.

Mercedes engineer from the caravan, monitoring who knows what.

Equipment Considerations

To be fair, both manufacturers pushed the envelope a bit on what appear to be rules outlining self-sufficiency. The Mercedes was absolutely packed with spare parts, stored meticulously where the back seat should have been, radiators, headlights, you name it, all carried on board.

A back seat full of spares. No doubt, a tricky way to get around rules governing self-sufficiency

Subaru started with Legacy RS BC5 which might seem unfair starting with a lightweight special edition (they were RHD) but on the same vein, the 2.3-16 was, itself a special car. I’m going to call this a draw. Subaru used a different, aerodynamic grille which probably dropped the cd of the car which, in stock form is .33 according to my sleuthing. Subaru also used disk wheels while Mercedes used standard wheels. Credit to Mercedes here because their standard wheels were designed to be very aerodynamic. Mercedes 190e 16v carries a slightly better cd at .30.

Mercedes changed 5th gear to get higher speed which to me feels like a bit of a stretch. They also removed reverse which is mad but it gained them a half mph I think with less rotating mass. Along with that, I also read that the HVAC was either disabled or removed and the suspension was lowered for aerodynamics. Pretty smart. Both probably tested the limits of whatever FIA rules may have been in place for such an event.

The Race

During the race both companies enjoyed excellent reliability runs. Mercedes replaced tires in 5000 mile intervals for fronts, 10,000 mile intervals for the rears while Subaru did all 4 at 13,000 mile intervals. Both tracks seemed to be pretty easy on tires. Subaru employed 2 minute pit stops upon which drivers were changed. Mercedes opted for 5 minute stops. By the end of the 50,000km run, Mercedes had done 243 pit stops.

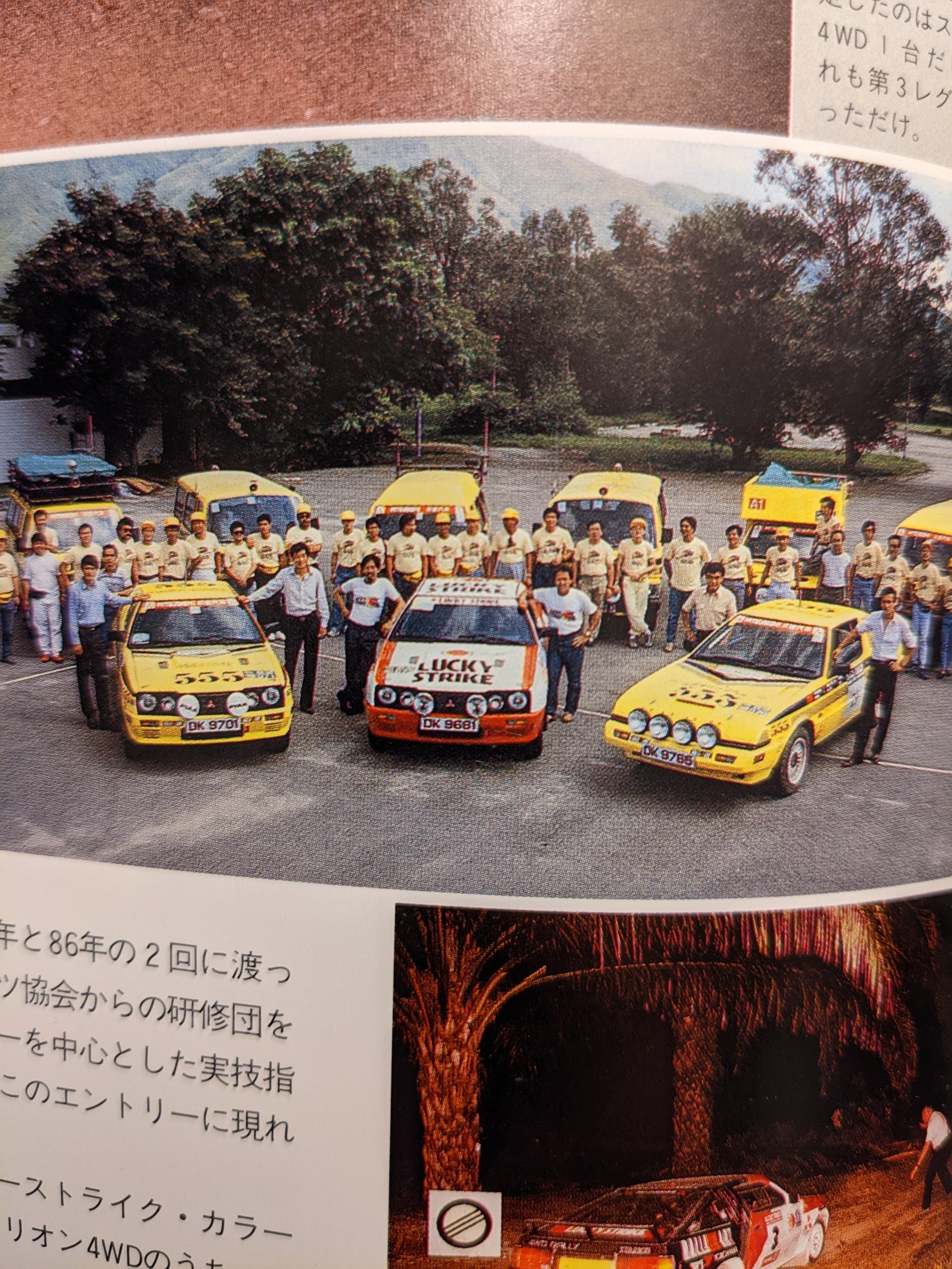

Services included removing bug screens from headlights and radiators for Mercedes, for Subaru similar. Both companies did oil changes. Mercedes claimed to have checked the valve adjustment in 5 minutes which seems wild. Subaru fueled from a cell in the trunk, as did Mercedes. Car colors were interesting. Subaru chose red, white and yellow for their three. A fourth silver car appears in this video and there was mention of a pace “rabbit” perhaps that was it. Mercedes chose green, white and red for their cars. The Mercedes were all painted in smoke-silver but they carried those colors on vinyl stickers on the rear windows and headlights.

I couldn’t find much controversy about Subaru’s run but Mercedes ran into a faulty distributor arm during their event. It was repaired with two-part epoxy successfully but not without scrutiny. You can read more about that detail here in this great write up from 1983’s Austrian Auto Revue Magazine . A nice detail about Subaru’s team and drivers was included in this Japanese Nostalgic Car article about Noriuki Koseki who was not only one of the endurance drivers but also the man considered to be the godfather of STI. The car is still on display at his son’s Subaru dealership Kit Service.

You need to do yourself a favor and watch both of these videos.

Panache Rating

It had to be done; I had to give each team a style rating and this might be the hardest bit of comparison to come. Mercedes won on the videography. The dark, moody lighting of their documentary, the car running at night, the sunrise at Nardo, the hot burning eclipse behind them, as well as the one underneath their tires, it was all very dramatic. The backside of the 2.3-16, covered in it’s own waste and thousands of miles of grit looked fantastic. There were a few bits in the Subaru video that I enjoyed a lot too. The man listening to the car with his hand cupped to his ear, we see this in hundreds of Japanese car videos to come. Iconic moment. Also, there was a nice montage of the Subaru running that I appreciated. Subaru really nailed it on the clothing, jackets to match each color car. The planning was impeccable.

Could the Mercedes have doubled it’s distance and survived? After all, Mercedes did hold154mph vs Subaru’s138mph…. highway stormer versus a rumbly rally car. We all knew that Subaru weren’t long-legged highway killers but I can be more confident wringing out my EJ20g Impreza for a few hours on a road trip knowing that it did that for 18 days straight. We should take a moment to imagine driving a 2.3-16 at redline for 4 days without stopping. How awesome that must have been. Or perhaps just as exciting, being a part of a multinational team in one of the first high-profile motorsport events for Subaru in the US. Marketing managers, engineers, accessory designers, all fighting for one goal. It’s a very cool thing to imagine.